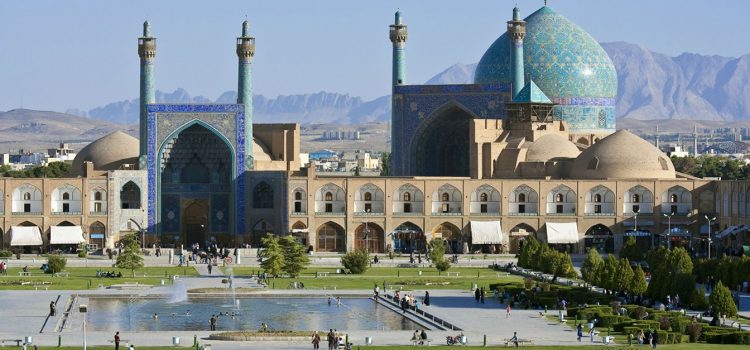

[:en]Meidan Emam, Esfahan[:de]Meidan Emam , Isfahan[:fr]Meidan Emam, Esfahan[:]

[:en]Built by Shah Abbas I the Great at the beginning of the 17th century, and bordered on all sides by monumental buildings linked by a series of two-storeyed arcades, the site is known for the Royal Mosque, the Mosque of Sheykh Lotfollah, the magnificent Portico of Qaysariyyeh and the 15th-century Timurid palace. They are an impressive testimony to the level of social and cultural life in Persia during the Safavid era.

Outstanding Universal Value

Brief Synthesis

The Meidan Emam is a public urban square in the centre of Esfahan, a city located on the main north-south and east-west routes crossing central Iran. It is one of the largest city squares in the world and an outstanding example of Iranian and Islamic architecture. Built by the Safavid shah Abbas I in the early 17th century, the square is bordered by two-storey arcades and anchored on each side by four magnificent buildings: to the east, the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque; to the west, the pavilion of Ali Qapu; to the north, the portico of Qeyssariyeh; and to the south, the celebrated Royal Mosque. A homogenous urban ensemble built according to a unique, coherent, and harmonious plan, the Meidan Emam was the heart of the Safavid capital and is an exceptional urban realisation.

Also known as Naghsh-e Jahan (“Image of the World”), and formerly as Meidan-e Shah, Meidan Emam is not typical of urban ensembles in Iran, where cities are usually tightly laid out without sizeable open spaces. Esfahan’s public square, by contrast, is immense: 560 m long by 160 m wide, it covers almost 9 ha. All of the architectural elements that delineate the square, including its arcades of shops, are aesthetically remarkable, adorned with a profusion of enamelled ceramic tiles and paintings.

Of particular interest is the Royal Mosque (Masjed-e Shah), located on the south side of the square and angled to face Mecca. It remains the most celebrated example of the colourful architecture which reached its high point in Iran under the Safavid dynasty (1501-1722; 1729-1736). The pavilion of Ali Qapu on the west side forms the monumental entrance to the palatial zone and to the royal gardens which extend behind it. Its apartments, high portal, and covered terrace (tâlâr) are renowned. The portico of Qeyssariyeh on the north side leads to the 2-km-long Esfahan Bazaar, and the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque on the east side, built as a private mosque for the royal court, is today considered one of the masterpieces of Safavid architecture.

The Meidan Emam was at the heart of the Safavid capital’s culture, economy, religion, social power, government, and politics. Its vast sandy esplanade was used for celebrations, promenades, and public executions, for playing polo and for assembling troops. The arcades on all sides of the square housed hundreds of shops; above the portico to the large Qeyssariyeh bazaar a balcony accommodated musicians giving public concerts; the tâlâr of Ali Qapu was connected from behind to the throne room, where the shah occasionally received ambassadors. In short, the royal square of Esfahan was the preeminent monument of Persian socio-cultural life during the Safavid dynasty.

Criterion (i): The Meidan Emam constitutes a homogenous urban ensemble, built over a short time span according to a unique, coherent, and harmonious plan. All the monuments facing the square are aesthetically remarkable. Of particular interest is the Royal Mosque, which is connected to the south side of the square by means of an immense, deep entrance portal with angled corners and topped with a half-dome, covered on its interior with enamelled faience mosaics. This portal, framed by two minarets, is extended to the south by a formal gateway hall (iwan) that leads at an angle to the courtyard, thereby connecting the mosque, which in keeping with tradition is oriented northeast/southwest (towards Mecca), to the square’s ensemble, which is oriented north/south. The Royal Mosque of Esfahan remains the most famous example of the colourful architecture which reached its high point in Iran under the Safavid dynasty. The pavilion of Ali Qapu forms the monumental entrance to the palatial zone and to the royal gardens which extend behind it. Its apartments, completely decorated with paintings and largely open to the outside, are renowned. On the square is its high portal (48 metres) flanked by several storeys of rooms and surmounted by a terrace (tâlâr) shaded by a practical roof resting on 18 thin wooden columns. All of the architectural elements of the Meidan Imam, including the arcades, are adorned with a profusion of enamelled ceramic tiles and with paintings, where floral ornamentation is dominant – flowering trees, vases, bouquets, etc. – without prejudice to the figurative compositions in the style of Riza-i Abbasi, who was head of the school of painting at Esfahan during the reign of Shah Abbas and was celebrated both inside and outside Persia.

Criterion (v): The royal square of Esfahan is an exceptional urban realisation in Iran, where cities are usually tightly laid out without open spaces, except for the courtyards of the caravanserais (roadside inns). This is an example of aform of urban architecture that is inherently vulnerable.

Criterion (vi): The Meidan Imam was the heart of the Safavid capital. Its vast sandy esplanade was used for promenades, for assembling troops, for playing polo, for celebrations, and for public executions. The arcades on all sides housed shops; above the portico to the large Qeyssariyeh bazaar a balcony accommodated musicians giving public concerts; the tâlâr of Ali Qapu was connected from behind to the throne room, where the shah occasionally received ambassadors. In short, the royal square of Esfahan was the preeminent monument of Persian socio-cultural life during the Safavid dynasty (1501-1722; 1729-1736).

Integrity

Within the boundaries of the property are located all the elements and components necessary to express the Outstanding Universal Value of the property, including, among others, the public urban square and the two-storey arcades that delineate it, the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque, the pavilion of Ali Qapu, the portico of Qeyssariyeh, and the Royal Mosque.

Threats to the integrity of the property include economic development, which is giving rise to pressures to allow the construction of multi-storey commercial and parking buildings in the historic centre within the buffer zone; road widening schemes, which threaten the boundaries of the property; the increasing number of tourists; and fire.

Authenticity

The historical monuments at Meidan Emam, Esfahan, are authentic in terms of their forms and design, materials and substance, locations and setting, and spirit. The surface of the public urban square, once covered with sand, is now paved with stone. A pond was placed at the centre of the square, lawns were installed in the 1990s, and two entrances were added to the northeastern and western ranges of the square. These and future renovations, undertaken by Cultural Heritage experts, nonetheless employ domestic knowledge and technology in the direction of maintaining the authenticity of the property.

Management and Protection requirements

Meidan Emam, Esfahan, which is public property, was registered in the national list of Iranian monuments as item no. 102 on 5 January 1932, in accordance with the National Heritage Protection Law (1930, updated 1998) and theIranian Law on the Conservation of National Monuments (1982). Also registered individually are the Royal Mosque (Masjed-e Shah) (no. 107), Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque (no. 105), Ali Qapu pavilion (no. 104), and Qeyssariyeh portico (no. 103). The inscribed World Heritage property, which is owned by the Government of Iran, and its buffer zone are administered and supervised by the Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization (which is administered and funded by the Government of Iran), through its Esfahan office. The square enclosure belongs to the municipality; the bazaars around the square and the shops in the square’s environs are owned by the Endowments Office. There is a comprehensive municipal plan, but no Management Plan for the property. Financial resources (which are recognised as being inadequate) are provided through national, provincial, and municipal budgets and private individuals.

Sustaining the Outstanding Universal Value of the property over time will require developing, approving, and implementing a Management Plan for the property, in consultation with all stakeholders, that defines a strategic vision for the property and its buffer zone, considers infrastructure needs, and sets out a process to assess and control major development projects, with the objective of ensuring that the property does not suffer from adverse effects of development.[:de]Es wurde Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts von Shah Abbas I. dem Großen erbaut .Es ist an allen Seiten von monumentalen Gebäuden, die durch eine Reihe von zweistöckigen Arkaden miteinander verbunden sind umgeben. Die Stätte umfasst die Königliche Moschee, die Moschee von Sheykh Lotfollah, der Prächtige Portikus von Qaysariyyeh und der Timurid Palast aus dem 15. Jahrhundert. Sie sind ein eindrucksvolles Zeugnis des sozialen und kulturellen Lebens in Persien während der Safawidenzeit.

Hervorragender universeller Wert

Kurze Zusammensetzung

Das Meidan Emam ist ein öffentlicher städtischer Platz im Zentrum von Isfahan, eine Stadt an den wichtigsten Nord-Süd- und Ost-West-Routen durch den zentralen Iran. Es ist einer der größten Stadtplätze der Welt und ein herausragendes Beispiel für iranische und islamische Architektur. Der Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts vom Safawiden-Schah Abbas I. erbaute Platz wird von zweistöckigen Arkaden begrenzt und an jeder Seite von vier prächtigen Gebäuden umgeben. Im Osten befindet sich die Scheich-Lotfallah-Moschee, im Westen der Pavillon von Ali Qapu, im Norden der Portikus von Qeyssariyeh,und im Süden die berühmte Königliche Moschee. Ein homogenes städtisches Ensemble, das nach einem einzigartigen, zusammenhängenden und harmonischen Plan erbaut wurde. Das Meidan Emam war das Herz der Safawiden-Hauptstadt und eine außergewöhnliche städtebauliche Zusammensetzung.

Auch bekannt als Naghsh-e Jahan (“Bild der Welt”), oder früher als Meidan-e Shah, ist Meidan Emam nicht typisch für städtische Ensembles im Iran, wo Städte normalerweise ohne große offene Räume eng aneinander liegen. Der öffentliche Platz von Isfahan ist dagegen immens: 560 m lang und 160 m breit, er umfasst fast 9 ha. Alle architektonischen Elemente, die den Platz beschreiben, einschließlich der Arkaden von Geschäften sind mit einer Fülle von emaillierten Keramikfliesen und Gemälden ästhetisch bemerkenswert geschmückt.Von besonderem Interesse ist die Königliche Moschee (Masjed-e Shah), die sich auf der Südseite des Platzes befindet und nach Mekka ausgerichtet ist. Es ist das berühmteste Beispiel der farbenfrohen Architektur, die im Iran unter der Safawiden-Dynastie (1501-1722; 1729-1736) ihren Höhepunkt erreichte. Der Pavillon von Ali Qapu an der Westseite bildet den monumentalen Eingang zur palastartigen Zone und zu den dahinter liegenden königlichen Gärten. Seine Wohnungen, hohes Portal und überdachte Terrasse (Tâlâr) sind bekannt. Der Portikus von Qeyssariyeh an der Nordseite führt zum 2 km langen Isfahan Basar und die Sheikh Lotfallah Moschee, die als private Moschee für den Königshof erbaut wurde.Sie gilt heute als eines der Meisterwerke der Safawiden-Architektur.

Das Meidan Emam war das Herzstück der Kultur, Wirtschaft, Religion, sozialen Macht, Regierung und Politik der Safawiden. Seine ausgedehnte sandige Esplanade wurde für Feiern, Promenaden und öffentliche Hinrichtungen, das Spielen von Polo und für das Zusammenstellen von Truppen genutzt. Die Arkaden auf allen Seiten des Platzes beherbergten Hunderte von Geschäften.

Kriterium (i): Das Meidan Emam stellt ein homogenes städtisches Ensemble, das über einen kurzen Zeitraum nach einem einzigartigen, zusammenhängenden und harmonischen Plan aufgebaut wurde ,dar. Alle dem Platz zugewandten Denkmäler sind ästhetisch bemerkenswert. Von besonderem Interesse ist die Königliche Moschee, die mit der Südseite des Platzes durch ein riesiges, tiefes Eingangsportal mit abgewinkelten Ecken verbunden ist.Sie ist mit einer Halbkuppel gekrönt, und innen ist mit emaillierten Fayence-Mosaiken bedeckt. Dieses von zwei Minaretten umrahmte Portal wird im Süden von einer formalen Torhalle (Iwan), die schräg zum Hof führt, erweitert und dadurch die Moschee verbindet, und traditionsgemäß nach Nordost / Südwest (Richtung Mekka) ausgerichtet ist. Die Königliche Moschee von Isfahan bleibt das berühmteste Beispiel der farbenfrohen Architektur, die ihren Höhepunkt im Iran unter der Safawiden-Dynastie erreichte.Seine vollständig mit Malereien geschmückten und nach außen weitgehend offenen Wohnungen sind bekannt. Auf dem Platz befindet sich das hohe Portal (48 Meter), das von mehreren Stockwerken flankiert und von einer Terrasse (Tâlâr)überragt wird ,die von einem praktischen Dach,das auf 18 dünnen Holzsäulen beschattet wird,ruht. Alle architektonischen Elemente des Meidan Imam sind mit einer Fülle von emaillierten Keramikfliesen und mit Gemälden – blühenden Bäumen, Vasen, usw., unbeschadet der figurativen Kompositionen in der Stil von Riza-i Abbasi, der während der Regierungszeit von Shah Abbas die Schule der Malerei in Isfahan leitete,geschmückt.

Kriterium (v): Der königliche Platz von Isfahan ist eine außergewöhnliche städtebauliche Realisierung im Iran, wo die Städte mit Ausnahme der Höfe der Karawansereien(Starssengasthöfe) normalerweise eng ohne Freiflächen angelegt sind.Dies ist ein Beispiel für eine Form der städtischen Architektur, die an sich anfällig ist.

Kriterium (vi): Der Meidan-Imam war das Herz der Safawiden-Hauptstadt. Seine ausgedehnte sandige Esplanade wurde für Promenaden, das Zusammenstellen von Truppen, Polospielen, Feiern und für öffentliche Hinrichtungen benutzt. Die Arkaden an allen Seiten beherbergten Geschäfte. Über dem Portikus zum großen Qeyssariyeh-Basar beherbergte ein Balkon für Musiker, die öffentliche Konzerte gaben. Der Tâlâr von Ali Qapu war von hinten mit dem Thronsaal , wo der Schah gelegentlich Botschafter empfing,verbunden. Kurz gesagt: Der königliche Platz von Isfahan war das bedeutendste Denkmal des persischen soziokulturellen Lebens während der Safawiden Dynastie (1501-1722; 1729-1736).

Integrität

Innerhalb der Grenzen des Eigentums befinden sich alle Elemente und Komponenten, die notwendig sind, um den außergewöhnlichen universellen Wert des Eigentums auszudrücken.Zu den Bedrohungen für die Integrität der Anlage gehören die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung, der Druck auf den Bau von mehrstöckigen Geschäfts- und Parkgebäuden im historischen Zentrum innerhalb der Pufferzone . Straßenerweiterungen, die steigenden Anzahl von Touristen und Feuer bedrohen die Ganzen Anlage.

Authentizität

Die historischen Denkmäler in Meidan Emam sind authentisch in Bezug auf ihre Formen und Design, Materialien und Substanz, Orte und Umgebung und Geist. Die Oberfläche des öffentlichen städtischen Platzes, einst mit Sand bedeckt, ist jetzt mit Steinen gepflastert. Ein Teich wurde in der Mitte des Platzes platziert. Rasen wurde in den 1990er Jahren installiert, und zwei Eingänge wurden in den nordöstlichen und westlichen Bereichen des Platzes hinzugefügt. Diese und zukünftige Renovierungen, die von Experten der Organisation für Kulturerbes durchgeführt werden, setzen dennoch heimisches Wissen und Technologie ein, um die Authentizität der Anlage zu bewahren.

Management- und Schutzanforderungen.

Meidan Emam, Isfahan ist ein öffentliches Eigentum.Es wurde am 5. Januar 1932 unter Nr.102 in die nationale Liste der iranischen Monumente als Artikel Nr. 1 eingetragen. Die Eintragung war in Übereinstimmung mit dem nationales Denkmalschutzrecht(1930,aktualisiert 1998) und dem iranischen Gesetz zur Erhaltung der nationalen Denkmäler (1982). Ebenfalls einzeln registriert sind die Königliche Moschee (Masjed-e Shah) (Nr. 107), die Scheich Lotfallah Moschee (Nr. 105), Ali Qapu Pavillon (Nr. 104) und Qeyssariyeh Portikus (Nr. 103). Die denkmalgeschützte Welterbestätte, die der iranischen Regierung gehört,wird von der iranischen Organisation für Kulturerbe, Handwerk und Tourismus,die ihr Büro in Isfahan hat, verwaltet und finanziert. Das quadratische Gehege gehört zur Gemeinde. Die Basare rund um den Platz und die Geschäfte in der Umgebung des Platzes sind Eigentum des Stiftungsamtes. Es gibt einen umfassenden kommunalen Plan, aber keinen Managementplan für die Immobilie. Finanzielle Ressourcen (die als unzureichend anerkannt werden) werden durch nationale, provinzielle und kommunale Haushalte und Privatpersonen bereitgestellt. Um den außergewöhnlichen universellen Wert der Immobilie im Laufe der Zeit zu erhalten, muss in Absprache mit allen Beteiligten ein Managementplan, der eine strategische vision für die Immobilie und ihre Pufferzone infrastruckturbedürfnisse berücksichtigt und festlegt , entwickelt und umgesetzt werden. Der Plan muß ein Prozes zur Bewertung und Kontrolle wichtiger Entwicklungsprojekte haben,und sicherstellen,daß die Immobilie nicht unter Auswirkungen der Entwicklung leidet.[:fr][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Construit par Shah Abbas Ier le Grand au début du XVIIe siècle et bordé de toutes parts par des bâtiments monumentaux reliés par une série d’arcades à deux étages, le site est connu pour la mosquée royale, la mosquée Sheykh Lotfollah, le magnifique portique de Qaysariyyeh et le palais timuride du XVe siècle. Ils constituent un témoignage impressionnant du niveau de vie sociale et culturelle en Perse à l’époque des Safavides.

Valeur universelle exceptionnelle

Brève synthèse

La place Emam est une place publique urbaine située au centre d’Ispahan, une ville située sur les routes principales nord-sud et est-ouest traversant le centre de l’Iran. C’est l’une des plus grandes places au monde et un exemple exceptionnel d’architecture iranienne et islamique. Construite par le shah safavide Shah Abbas Ier au début du XVIIe siècle, la place est bordée d’arcades à deux étages et ancrée de part et d’autre par quatre magnifiques bâtiments: à l’est, la mosquée Sheikh Lotfallah; à l’ouest, le pavillon d’Ali Qapu; au nord, le portique de Qeyssariyeh; et au sud, la célèbre mosquée royale. Ensemble urbain homogène construit selon un plan unique, cohérent et harmonieux, le Meidan Emam était le cœur de la capitale Safavide et constitue une réalisation urbaine exceptionnelle.

Également connu sous le nom de Naghsh-e Jahan («Image du monde»), et autrefois sous le nom de Meidan-e Shah, Meidan Emam n’est pas typique des ensembles urbains en Iran, où les villes sont généralement étroites sans espaces ouverts de grande taille. La place publique d’Ispahan, en revanche, est immense: 560 m de long sur 160 m de large, elle couvre près de 9 ha. Tous les éléments architecturaux qui délimitent la place, y compris ses arcades de boutiques, sont esthétiquement remarquables, ornés d’une profusion de carreaux de céramique émaillée et de peintures.

La mosquée royale (Masjed-e Shah), située du côté sud de la place et faisant face à la Mecque, présente un intérêt particulier. Il reste l’exemple le plus célèbre de l’architecture colorée qui a atteint son apogée en Iran sous la dynastie des Safavides (1501-1722; 1729-1736). Le pavillon Ali Qapu sur le côté ouest constitue l’entrée monumentale de la zone des palais et des jardins royaux qui s’étendent derrière celle-ci. Ses appartements, son haut portail et sa terrasse couverte (tâlâr) sont réputés. Le portique de Qeyssariyeh, au nord, mène au bazar Esfahan, long de 2 km. La mosquée Sheikh Lotfallah, située à l’est, a été construite comme une mosquée privée pour la cour royale. Elle est aujourd’hui considérée comme l’un des chefs-d’œuvre de l’architecture safavide.

Critère (i): La place Emam constitue un ensemble urbain homogène, construit sur une courte période selon un plan unique, cohérent et harmonieux. Tous les monuments qui font face à la place sont esthétiquement remarquables. La mosquée royale présente un intérêt particulier. Elle est reliée au côté sud de la place par un immense portail d’entrée profond aux angles inclinés et surmonté d’un demi-dôme recouvert à l’intérieur de mosaïques en faïence émaillée. Ce portail, encadré par deux minarets, est prolongé au sud par un portail d’entrée (iwan) qui forme un angle avec la cour et relie ainsi la mosquée qui, conformément à la tradition, est orientée nord-ouest / sud-ouest (vers La Mecque), à l’ensemble de la place, qui est orienté nord / sud. La mosquée royale d’Ispahan reste l’exemple le plus célèbre de l’architecture colorée qui a atteint son apogée en Iran sous la dynastie des Safavides. Le pavillon d’Ali Qapu constitue l’entrée monumentale de la zone des palais et des jardins royaux qui la prolongent. Ses appartements, entièrement décorés de peintures et largement ouverts sur l’extérieur, sont réputés. Sur la place se trouve son haut portail (48 mètres) flanqué de plusieurs étages de salles et surmonté d’une terrasse (tâlâr) ombragée par un toit pratique reposant sur 18 minces colonnes de bois. Tous les éléments architecturaux de la place imam, y compris les arcades, sont ornés d’une profusion de carreaux de céramique émaillée et de peintures où l’ornement floral est dominant – arbres à fleurs, vases, bouquets, etc. – sans préjudice des compositions figuratives du style de Riza-i Abbasi, qui était à la tête de l’école de peinture à Ispahan pendant le règne de Shah Abbas, a été célébré à l’intérieur et à l’extérieur de la Perse.

Critère (ii): La place royale d’Ispahan est une réalisation urbaine exceptionnelle en Iran, où les villes sont généralement bien aménagées, sans espaces ouverts, à l’exception des cours intérieures des caravansérails. C’est un exemple d’architecture urbaine vulnérable par nature.

Critère (iii): la place Imam était le cœur de la capitale safavide. Son vaste esplanade de sable était utilisée pour les promenades, le rassemblement des troupes, le polo, les fêtes et les exécutions publiques. Les arcades de tous les côtés abritaient des magasins; au-dessus du portique du grand bazar Qeyssariyeh, un balcon accueillait des musiciens donnant des concerts publics; le tâlâr d’Ali Qapu était relié par l’arrière à la salle du trône, où le shah recevait parfois des ambassadeurs. En bref, la place royale d’Ispahan était le monument prééminent de la vie socioculturelle perse de la dynastie des Safavides (1501-1722; 1729-1736).

Intégrité

Tous les éléments et composants nécessaires à l’expression de la valeur universelle exceptionnelle du bien sont localisés à l’intérieur du bien, y compris, entre autres, la place publique et les arcades à deux étages qui le délimitent, la mosquée Sheikh Lotfallah, le pavillon Ali Qapu, le portique de Qeyssariyeh et la mosquée royale.

Les menaces qui pèsent sur l’intégrité du bien incluent le développement économique, qui crée des pressions pour permettre la construction de bâtiments commerciaux et de parkings à plusieurs étages dans le centre historique de la zone tampon; les projets d’élargissement des routes, qui menacent les limites du bien; le nombre croissant de touristes; et le feu.

Authenticité

Les monuments historiques de Meidan Emam, Esfahan, sont authentiques par leurs formes et leur conception, leurs matériaux et leur matière, leur emplacement, leur cadre et leur esprit. La surface de la place publique urbaine, autrefois recouverte de sable, est maintenant pavée de pierre. Un étang a été placé au centre de la place, des pelouses ont été installées dans les années 1990 et deux entrées ont été ajoutées aux rangées nord-est et ouest de la place. Ces rénovations et celles à venir, entreprises par des experts du patrimoine culturel, utilisent néanmoins des connaissances et des technologies nationales visant à préserver l’authenticité du bien.

Exigences de gestion et de protection

La place Emam, Ispahan, propriété publique, a été inscrit sur la liste nationale des monuments iraniens sous le numéro d’article. 102 le 5 janvier 1932, conformément à la loi sur la protection du patrimoine national (1930, mise à jour en 1998) et à la loi iranienne sur la conservation des monuments nationaux (1982). La mosquée royale (Masjed-e Shah) (n ° 107), la mosquée Cheikh Lotfallah (n ° 105), le pavillon Ali Qapu (n ° 104) et le portique de Qeyssariyeh (n ° 103) sont également inscrits à titre individuel. Le bien inscrit au patrimoine mondial, qui appartient au gouvernement iranien, et sa zone tampon sont administrés et supervisés par l’Organisation iranienne pour le patrimoine culturel, l’artisanat et le tourisme (qui est administrée et financée par le gouvernement iranien), par l’intermédiaire de son bureau d’Ispahan.L’enceinte carrée appartient à la municipalité; les bazars autour de la place et les magasins dans les environs de la place appartiennent au bureau des dotations. Il existe un plan municipal complet, mais aucun plan de gestion pour la propriété. Les ressources financières (considérées comme insuffisantes) proviennent des budgets nationaux, provinciaux et municipaux et de particuliers.

La préservation de la valeur universelle exceptionnelle du bien au fil du temps nécessitera l’élaboration, l’approbation et la mise en œuvre d’un plan de gestion du bien, en consultation avec toutes les parties prenantes, qui définisse une vision stratégique du bien et de sa zone tampon, prenne en compte les besoins en infrastructure et définisse mettre en place un processus d’évaluation et de contrôle des grands projets de développement, dans le but de s’assurer que le bien ne subit pas les effets négatifs du développement.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][:]

[:en]Tchogha Zanbil[:de]Tschogha Zambil[:fr]Tchogha Zanbil[:]

[:en]

The ruins of the holy city of the Kingdom of Elam, surrounded by three huge concentric walls, are found at Tchogha Zanbil. Founded c. 1250 B.C., the city remained unfinished after it was invaded by Ashurbanipal, as shown by the thousands of unused bricks left at the site.

Brief Synthesis

Located in ancient Elam (today Khuzestan province in southwest Iran), Tchogha Zanbil (Dur-Untash, or City of Untash, in Elamite) was founded by the Elamite king Untash-Napirisha (1275-1240 BCE) as the religious centre of Elam. The principal element of this complex is an enormous ziggurat dedicated to the Elamite divinities Inshushinak and Napirisha. It is the largest ziggurat outside of Mesopotamia and the best preserved of this type of stepped pyramidal monument. The archaeological site of Tchogha Zanbil is an exceptional expression of the culture, beliefs, and ritual traditions of one of the oldest indigenous peoples of Iran. Our knowledge of the architectural development of the middle Elamite period (1400-1100 BCE) comes from the ruins of Tchogha Zanbil and of the capital city of Susa 38 km to the north-west of the temple).

The archaeological site of Tchogha Zanbil covers a vast, arid plateau overlooking the rich valley of the river Ab-e Diz and its forests. A “sacred city” for the king’s residence, it was never completed and only a few priests lived there until it was destroyed by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal about 640 BCE. The complex was protected by three concentric enclosure walls: an outer wall about 4 km in circumference enclosing a vast complex of residences and the royal quarter, where three monumental palaces have been unearthed (one is considered a tomb-palace that covers the remains of underground baked-brick structures containing the burials of the royal family); a second wall protecting the temples (Temenus); and the innermost wall enclosing the focal point of the ensemble, the ziggurat.

The ziggurat originally measured 105.2 m on each side and about 53 m in height, in five levels, and was crowned with a temple. Mud brick was the basic material of the whole ensemble. The ziggurat was given a facing of baked bricks, a number of which have cuneiform characters giving the names of deities in the Elamite and Akkadian languages. Though the ziggurat now stands only 24.75 m high, less than half its estimated original height, its state of preservation is unsurpassed. Studies of the ziggurat and the rest of the archaeological site of Tchogha Zanbil containing other temples, residences, tomb-palaces, and water reservoirs have made an important contribution to our knowledge about the architecture of this period of the Elamites, whose ancient culture persisted into the emerging Achaemenid (First Persian) Empire, which changed the face of the civilised world at that time.

Criterion (iii): The ruins of Susa and of Tchogha Zanbil are the sole testimonies to the architectural development of the middle Elamite period (1400-1100 BCE).

Criterion (iv): The ziggurat at Tchogha Zanbil remains to this day the best preserved monument of this type and the largest outside of Mesopotamia.

Integrity

Within the boundaries of the property are located all the elements and components necessary to express the Outstanding Universal Value of the property, including, among others, the concentric walls, the royal quarter, the temples, various dependencies, and the ziggurat. Almost none of the various architectural elements and spaces has been removed or suffered major damage. The integrity of the landscape and lifestyle of the indigenous communities has largely been protected due to being away from urban areas.

Identified threats to the integrity of the property include heavy rainfalls, which can have a damaging effect on exposed mud-brick structures; a change in the course of the river Ab-e Diz, which threatens the outer wall; sugar cane cultivation and processing, which have altered traditional land use and increased air and water pollution; and deforestation of the river valleys. Visitors were banned from climbing the ziggurat in 2002, and a lighting system has been installed and guards stationed at the site to protect it from illegal excavations.

Authenticity

The historical monuments of the archaeological site of Tchogha Zanbil are authentic in terms of their forms and design, materials and substance, and locations and setting. Several conservation measures have been undertaken since the original excavations of the site between 1946 and 1962, but they have not usually disturbed its historical authenticity.

Protection and management requirements

Tchogha Zanbil was registered in the national list of Iranian monuments as item no. 895 on 26 January 1970. Relevant national laws and regulations concerning the property include the National Heritage Protection Law (1930, updated 1998) and the 1980 Legal bill on preventing clandestine diggings and illegal excavations. The inscribed World Heritage property, which is owned by the Government of Iran, and its buffer zone are administered by the Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization (which is administered and funded by the Government of Iran). A Management Plan was prepared in 2003 and has since been implemented. Planning for tourism management, landscaping, and emergency evacuation for the property has been accomplished and implementation was in progress in 2013. A research centre has undertaken daily, monthly, and annual monitoring of the property since 1998. Financial resources for Tchogha Zanbil are provided through national budgets.

Conservation activities have been undertaken within a general framework, including development of scientific research programs; comprehensive conservation of the property and its natural-historical context; expansion of the conservation program to the surrounding environment; concentration on engaging the public and governmental organizations and agencies; and according special attention to programs for training and presentation (with the aim of developing cultural tourism) based on sustainable development. Objectives include research programs and promotion of a conservation management culture; scientific and comprehensive conservation of the property and surrounding area; and development of training and introductory programmes.

Sustaining the Outstanding Universal Value of the property over time will require creating a transparent and regular funding system, employing efficient and sustainable management systems, supporting continuous protection and presentation, enjoying the public support and giving life to the property, adopting a “minimum intervention” approach, and respecting the integrity and authenticity of the property and its surrounding environment. In addition, any outstanding recommendations of past expert missions to the property should be addressed.

[:de]

Die Ruinen der heiligen Stadt des Königreichs Elam,die von drei riesigen konzentrischen Mauern umgeben sind, befinden sich in Tschogha Zambil.Die Stadt wurde 1250 v.Chr. gegründet,und blieb unvollendet, nachdem sie von Assurbanipal überfallen worden war, wie die tausenden von unbenutzten Steinen auf der Baustelle zeigten.

Kurze Zusammensetzung

Tschogha Zambil(Dur-untash,die Stadt der Untash) liegt im alten Elam (heute Khuzestan eine Provinz im Südwesten Irans).Sie wurde vom elamitischen König Untash-Napirisha (1275-1240 v. Chr.) als religiöses Zentrum von Elam gegründet. Das Hauptelement dieses Komplexes ist eine riesige Zikkurat, die den elamitischen Gottheiten Inshushinak und Napirisha gewidmet ist. Es ist die größte Zikkurat außerhalb von Mesopotamien und das am besten erhaltene dieser Art von abgestuften Pyramiden-Denkmal. Die archäologische Stätte von Tschogha Zambil ist ein außergewöhnlicher Ausdruck der Kultur, des Glaubens und der rituellen Traditionen eines der ältesten indigenen Völker des Irans. Unser Wissen über die architektonische Entwicklung der mittleren elamischen Periode (1400-1100 v. Chr.) stammen aus den Ruinen von Tschogha Zambil und der Hauptstadt Susa 38 km nordwestlich des Tempels.

Die archäologische Stätte von Tschogha Zambil erstreckt sich über eine weite, trockene Hochebene mit Blick auf das fruchtbare Tal des Flusses Ab-e Diz und seine Wälder. Als “heilige Stadt” für die Residenz des Königs wurde sie nie vollendet . Nur wenige Priester lebten dort, bis sie etwa 640 v. Chr. Vom assyrischen König Assurbanipal zerstört wurde. Der Komplex wurde durch drei konzentrische Umfassungsmauern geschützt.Eine Außenmauer von etwa 4 km Umfang umfasste einen großen Komplex von Residenzen und das königliche Viertel, wo drei monumentale Paläste ausgegraben wurden(einer gilt als ein Grabpalast,der die Überreste des Untergrunds bedeckt). Backsteinstrukturen mit Bestattungen der königlichen Familie, eine zweite Mauer, die die Tempel schützt (Temenus), und die innerste Wand umschließt den Brennpunkt des Ensembles, die Zikkurat.

Die Zikkurat hatte ursprünglich 105,2 m auf jeder Seite und etwa 53 m Höhe in fünf Ebenen, und wurde mit einem Tempel gekrönt. Lehmziegel waren das Grundmaterial des gesamten Ensembles. Die Zikkurat erhielt eine Verkleidung aus gebrannten Ziegeln, von denen einige keilförmige Schriftzeichen, die die Namen von Gottheiten in den elamischen und akkadischen Sprachen enthalten. Obwohl die Zikkurat jetzt nur 24,75 m hoch ist( weniger als die Hälfte ihrer geschätzten ursprünglichen Höhe), ist ihr Erhaltungszustand unübertroffen. Untersuchungen der Zikkurat und der übrigen archäologischen Fundstätte von Tschogha Zambil mit anderen Tempeln, Residenzen, Grabpalästen und Wasserreservoiren haben einen wichtigen Beitrag zu unserem Wissen über die Architektur dieser Epoche der Elamites und das aufstrebende Achaemeniden Reich, das zu dieser Zeit das Gesicht der zivilisierten Welt veränderte,geleistet.

Kriterium (iii): Die Ruinen von Susa und Tschogha Zambil sind die einzigen Zeugnisse für die architektonische Entwicklung der mittleren elamischen Periode (1400-1100 v. Chr.).

Kriterium (iv): Die Zikkurat bei Tschogha Zambil ist bis heute das am besten erhaltene und größte Denkmal dieses Typs außerhalb von Mesopotamien.

Integrität

Innerhalb der Grenzen der Anlage befinden sich alle Elemente und Komponenten, die notwendig sind, um den außergewöhnlichen universellen Wert der Anlage einschließlich unter anderem der konzentrischen Wände, des königlichen Viertels, der Tempel,und der Zikkurat auszudrücken. Fast keines der verschiedenen architektonischen Elemente und Räume wurde entfernt oder schwer beschädigt. Die Integrität der Landschaft und des Lebensstils der indigenen Gemeinschaften wurde größtenteils dadurch geschützt, daß sie nicht in städtischen Gebieten leben.

Zu den identifizierten Bedrohungen für die Integrität des Grundstücks gehören starke Regenfälle, die sich auf freiliegende Lehmziegelstrukturen schädlich auswirken können,eine Veränderung im Verlauf des Flusses Ab-e Diz, der die Außenmauer bedroht, Zuckerrohranbau und -verarbeitung, die erhöhte Luft- und Wasserverschmutzung, und Abholzung der Flußtäler. Im Jahr 2002 wurde die Zikkurat zu besteigen verboten.Es wurde ein Beleuchtungssystem installiert und Wachen stationiert, um sie vor illegalen Ausgrabungen zu schützen.

Authentizität

Die historischen Denkmäler der archäologischen Stätte von Tschogha Zambil sind authentisch in Bezug auf ihre Formen und Design, Materialien und Substanz, und Orte und Umgebung. Seit den ursprünglichen Ausgrabungen des Geländes zwischen 1946 und 1962 wurden mehrere Erhaltungsmaßnahmen durchgeführt, die jedoch ihre historische Authentizität nicht gestört haben.

Schutz- und Managementanforderungen

Tschogha Zambil wurde in die nationale Liste der iranischen Monumente als Artikel Nr. 1 eingetragen. Die entsprechenden nationalen Gesetze und Vorschriften bezüglich des Grundstücks umfassen das Gesetz zum Schutz des nationalen Erbes (1930, aktualisiert 1998) und das Gesetzes von 1980 über die Verhinderung von illegalen Ausgrabungen. Die denkmalgeschützte Welterbestätte, die der iranischen Regierung gehört, werden von der iranischen Kultur-, Handwerks- und Tourismusorganisation verwaltet. Ein Managementplan wurde 2003 erstellt und seitdem umgesetzt. Die Planung für das Tourismusmanagement, die Landschaftsgestaltung und die Notfallevakuierung der Anlage wurde abgeschlossen ,und die Umsetzung wurde 2013 durchgeführt. Ein Forschungszentrum hat seit 1998 tägliche, monatliche und jährliche Überwachung der Anlage durchgeführt. Die finanziellen Mittel für Tschogha Zambil werden von nationalen Haushalten bereitgestellt .Naturschutzmaßnahmen wurden in einem allgemeinen Rahmen, einschließlich der Entwicklung von Forschungsprogrammen, umfassende Erhaltung der Anlage und ihres naturhistorischen Kontextes ,Erweiterung des Schutzprogramms auf die Umgebung,Konzentration auf die Einbeziehung der Öffentlichkeit und der staatlichen Organisationen und Agenturen durchgeführt. Zu den Zielen gehören Forschungsprogramme, die Förderung einer Kultur des Naturschutzmanagements,wissenschaftliche Erhaltung des Grundstücks und der Umgebung, und Entwicklung von Trainings- und Einführungsprogrammen.

Um den außergewöhnlichen universellen Wert der Immobilie im Laufe der Zeit aufrecht zu erhalten, muss ein transparentes und regelmäßiges Finanzierungssystem geschaffen werden, das effiziente und nachhaltige Managementsysteme verwendet, fortwährenden Schutz und Präsentation unterstützt, die öffentliche Unterstützung genießt und der Immobilie Leben einhaucht. Darüber hinaus sollten alle ausstehenden Empfehlungen früherer Expertenmissionen auf dem Grundstück behandelt werden.

[:fr][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

TCHOGHA ZANBIL

Les ruines de la ville sainte du royaume d’Elam, entourées de trois énormes murs concentriques, se trouvent à Tchogha Zanbil. Fondée c. 1250 av. J.-C., la ville reste inachevée après l’invasion d’Asurbanipal, comme le montrent les milliers de briques inutilisées laissées sur le site.

Tchogha Zanbil (Dur-Untash, ou la ville d’Unash, en élamite), située dans l’ancienne Élam (aujourd’hui province du Khuzestan, sud-ouest de l’Iran), a été fondée par le roi élamite, Untash-Napirisha (1275-1240 av. J.-C.), en tant que centre religieux d’Elam. L’élément principal de ce complexe est une énorme ziggourat dédiée aux divinités élamites Inshushinak et Napirisha. C’est la plus grande ziggourat en dehors de la Mésopotamie et la mieux conservée de ce type de monument pyramidal en gradins. Le site archéologique de Tchogha Zanbil est une expression exceptionnelle de la culture, des croyances et des traditions rituelles de l’un des plus anciens peuples autochtones d’Iran. Notre connaissance du développement architectural du milieu de la période élamite (1400-1100 av. J.-C.) provient des ruines de Tchogha Zanbil et de la capitale, Susa, située à 38 km au nord-ouest du temple.

Le site archéologique de Tchogha Zanbil couvre un vaste plateau aride surplombant la riche vallée de la rivière Ab-e Diz et ses forêts. Cité sacrée de la résidence du roi, elle n’a jamais été achevée et seuls quelques prêtres y ont vécu jusqu’à sa destruction par le roi assyrien Assurbanipal vers 640 av. Le complexe était protégé par trois murs d’enceinte concentriques: un mur extérieur d’environ 4 km de circonférence renfermant un vaste ensemble de résidences et le quartier royal, où trois palais monumentaux ont été découverts (l’un est considéré comme un palais des tombes qui recouvre les restes souterrains structures en briques cuites contenant les sépultures de la famille royale); un second mur protégeant les temples (Temenus); et le mur le plus profond entourant le point focal de l’ensemble, la ziggourat.

La ziggourat mesurait à l’origine 105,2 m de chaque côté et environ 53 m de haut, sur cinq niveaux, et était couronnée d’un temple. La brique de boue était le matériau de base de l’ensemble. La ziggourat a reçu un revêtement de briques cuites, dont un certain nombre ont des caractères cunéiformes donnant les noms de divinités en langues élamite et akkadienne. Bien que la ziggourat n’ait plus que 24,75 m de hauteur, soit moins de la moitié de sa hauteur initiale estimée, son état de conservation est inégalé. Les études de la ziggourat et du reste du site archéologique de Tchogha Zanbil contenant d’autres temples, résidences, palais des tombes et réservoirs d’eau ont grandement contribué à la connaissance que nous avons de l’architecture de cette période des Élamites, dont la culture ancienne a perduré l’émergence d’un empire achéménide (premier perse), qui changea la face du monde civilisé à cette époque.

Critère (i): Les ruines de Suse et de Tchogha Zanbil sont les seuls témoignages du développement architectural de la période du mi-élamite (1400-1100 av. J.-C.).

Critère (ii): La ziggourat de Tchogha Zanbil reste à ce jour le monument le mieux conservé de ce type et le plus grand en dehors de la Mésopotamie.

Intégrité

Tous les éléments et composants nécessaires à l’expression de la valeur universelle exceptionnelle du bien sont localisés à l’intérieur des limites du bien, notamment les murs concentriques, le quartier royal, les temples, diverses dépendances et la ziggurat. Presque aucun des divers éléments et espaces architecturaux n’a été enlevé ou a subi des dommages importants. L’intégrité du paysage et du mode de vie des communautés autochtones a été en grande partie protégée en raison de son éloignement des zones urbaines.

Les menaces identifiées pour l’intégrité du bien incluent les fortes précipitations, qui peuvent avoir un effet néfaste sur les structures en briques crues exposées; un changement dans le cours de la rivière Ab-e Diz, qui menace le mur extérieur; la culture et la transformation de la canne à sucre, qui ont modifié l’utilisation traditionnelle des terres et accru la pollution de l’air et de l’eau; et déforestation des vallées fluviales. Les visiteurs ont été interdits d’escalader la ziggurat en 2002 et un système d’éclairage a été installé et des gardes sont postés sur le site pour le protéger des fouilles illégales.

Authenticité

Les monuments historiques du site archéologique de Tchogha Zanbil sont authentiques par leurs formes et leur conception, leurs matériaux et leur substance, ainsi que par leur emplacement et leur cadre. Plusieurs mesures de conservation ont été entreprises depuis les fouilles initiales du site entre 1946 et 1962, mais elles n’ont généralement pas perturbé son authenticité historique.

Exigences de protection et de gestion

Tchogha Zanbil a été inscrit sur la liste nationale des monuments iraniens sous le numéro d’article. 895, le 26 janvier 1970. Les lois et règlements nationaux pertinents concernant le bien comprennent la loi sur la protection du patrimoine national (1930, mise à jour en 1998) et le projet de loi de 1980 sur la prévention des fouilles clandestines et des fouilles illégales. Le bien inscrit au patrimoine mondial, qui appartient au gouvernement iranien, et sa zone tampon sont administrés par l’Organisation iranienne pour le patrimoine culturel, l’artisanat et le tourisme (qui est administrée et financée par le gouvernement iranien). Un plan de gestion a été préparé en 2003 et a depuis été mis en œuvre. La planification de la gestion du tourisme, de l’aménagement paysager et de l’évacuation d’urgence du bien a été effectuée et sa mise en œuvre était en cours en 2013. Un centre de recherche effectue un suivi quotidien, mensuel et annuel du bien depuis 1998. Les ressources financières pour Tchogha Zanbil sont fournies par budgets nationaux.

Les activités de conservation ont été entreprises dans un cadre général, y compris l’élaboration de programmes de recherche scientifique; conservation intégrale du bien et de son contexte naturel et historique; extension du programme de conservation au milieu environnant; se concentrer sur la participation du public et des organisations et agences gouvernementales; et accorder une attention particulière aux programmes de formation et de présentation (visant à développer le tourisme culturel) basés sur le développement durable. Les objectifs comprennent des programmes de recherche et la promotion d’une culture de gestion de la conservation; conservation scientifique et globale du bien et de ses environs; et développement de programmes de formation et d’initiation.

La préservation de la valeur universelle exceptionnelle du bien à long terme nécessitera la création d’un système de financement transparent et régulier, utilisant des systèmes de gestion efficaces et durables, soutenant une protection et une présentation continues, bénéficiant de l’appui du public et donnant vie au bien, en adoptant une «intervention minimale». respectant l’intégrité et l’authenticité du bien et de son environnement. En outre, toutes les recommandations en suspens émanant de missions d’experts antérieures sur le bien devraient être examinées.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][:]